Pectus Carinatum

Pectus Carinatum (PC) is a thoracic deformity in which an abnormal costal cartilage growth produces an outward anterior chest wall protrusion described as “pigeon chest”.

PC is considered the second-most common cause of thoracic malformation after pectus excavatum (PE), with a reported incidence ranging from a fifth of PE in some centres, to arrive to an equal incidence in others. It is more prevalent in males with a ratio of 3-4 to 1.

PC is often noted in childhood with progression during adolescence.

PC malformations could be classified according to the shape of the protuberance in symmetric (photo 1) and asymmetric defect (photo 2) and in chondrogladiolar or chondromanubrial defect depending if the site of sternal angulation is located at the body of the sternum or at the manubrium. The chondrogladiolar is the more common one.

PC can be also a secondary malformation, occurring after sternotomies for cardiac surgery or following surgical PE repair.

Diagnosis is made by physical examination and the elasticity of the sternum and related deformed costal cartilages can always be assessed by manual compression or by means of pressure-measuring devices.

Photo 1: Symmetric PC Photo 2: Asymmetric Pcù

Author

Antonio Messineo, M.D.

References

Mantinez-Ferro et al. Seminar in Ped. Surgery. 2008

De Beer et al. Ann. Thorac. Surgery. 2017

Fraser et al. Ann. Thorac. Surgery. 2020

Quality of Life

Pectus carinatum often results in a reduced quality of life (QoL) due to a disturbed body image and lower self-esteem. Several studies have shown a significant reduction of QoL. After correction of the deformity, pectus patients had a significant improvement of QoL.

Author

Caroline Fortmann, M.D.

References

Paulson et al. J Pediatr Surg. 2019

Bostanci et al. J Pediatr Surg. 2013

Knudsen et al. J Pediatr Surg. 2015

Bracing

Over last years, bracing for pectus carinatum has gained significant popularity, and this has been corroborated by the increasing number of publications on bracing versus surgery. However, this form of therapy was not new as the first reports were published almost three decades ago. Most recent reviews, endorse bracing as first line treatment for pectus carinatum and it has demonstrated to be effective to treat both, symmetric and asymmetric cases.

A wide range of commercially available braces are available, some of them include pressure measuring capabilities although local orthotics departments are also capable of creating their own pectus carinatum braces.

It is highly likely that a bracing program is more important than the brace itself and prescribing a brace alone is unlikely to result in success. Continued follow-up during treatment, with frequent adjustments, assessment of patient progress, and maintenance of patient motivation, is essential.

Fig 1. Symmetric Pectus Carinatum: Results after 9 months of treatment of a 13-year-old patient with severe symmetric pectus carinatum using a Dynamic Compression System. Pressure of initial correction (PIC) 6,5 PSI

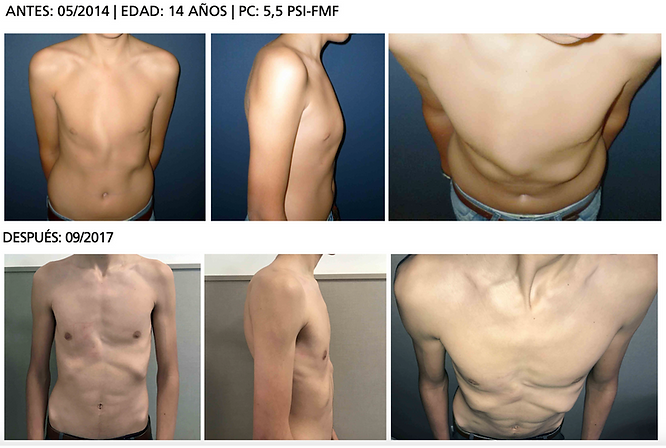

Fig 2. Asymmetric Pectus Carinatum: Results after one year of treatment with late follow-up pictures (2.5 years) of a 14-year-old patient with severe asymmetric pectus carinatum using a Dynamic Compression System. Pressure of initial correction (PIC) 5,5 PSI

Author

Marcelo Martinez-Ferro, M.D.

References

Haje et al. J Pediatr Orthop 1992

Martinez-Ferro et al. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2008

Emil et al. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2018

de Beer et al. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2018

Minimally-invasive repair of pectus carinatum

The criteria for selecting patients to be eligible for minimally-invasive repair of pectus carinatum (MIRPC) are mainly based on the elasticity of the thoracic wall. The ideal timeframe for the operation is the period of rapid body growth. Both symmetric and asymmetric clinical forms can be corrected using the MIRPC method.

In this technique, the sternochondral region is compressed by implanting a metal bar subcutaneously in the presternal region and securing it bilaterally to the posterolateral portion of the costal arches. The implant consists of a compression strut and fixation plates. The two fixation plates, which are fixed to the compression strut with screws, are rectangular in shape and have holes at the ends that allow the plates to be attached to the ribs by means of steel wire suture. Correction of the chest contour and simultaneous lateral expansion of the depressed costochondral arches are achieved by compressing the protruding anterior region of the chest wall. The strut remains implanted for 2 – 3 years.

Bar adherence to patient skin has been a frequent complication. It is highly recommended to concentrate in modeling the implant bar to match it as much as possible with the chest shape, to achieve a minimal contact with the skin.

Fig. 1: Model of the implanted bar and fixation plates on the ribcage

Fig 2a – 2c: Symmetric Pectus Carinatum: Results of 3 patients who underwent MIRPC (before and after correction)

Fig 3a & 3b: Asymmetric Pectus Carinatum: Results of 2 patients who underwent MIRPC (before and after correction)

Author: Horacio Abramson, MD

References

Abramson H. Arch Bronconeumol 2005

Abramson et al. J Pediatr Surg 2009

Geraedts et al. J Pediatr Surg 2022

Katrancioglu et al. Asian J Surg 2018

The Sandwich Technique

The sandwich technique is based on the press-molding to evenly remodel the chest wall, by applying counter-forces to compress the carinated portion and internal support to prevent the surrounding areas from being aggravated and ultimately the entire anterior chest wall to achieve an anatomically normal chest wall. The external bar applies pressure to compress the carinatum, while the internal bars provide support to the chest wall from underneath, resulting in a reshaped and flattened chest wall.

The primary repair target is marked on the top of the carinatum, with secondary targets on the depressed portions of the chest wall. First, the internal bars that conform the chest wall morphology are introduced using pectoscopic dissection. The internal bars are to elevate the depressed portion of the chest wall and support it against the upcoming external bar compression. The external bar, with a flattened segment for more compression on the carinated part, is placed subcutaneously onto the apex of the chest wall protrusion to press down on the carinatum. Finally, the external and internal bars are connected to the bridge plate while compressing the carinatum using a table-mounted compressor finally to form a fortress cage to squeeze (press-mold) the chest wall.

Parallel bar sandwiching: two internal bars in a parallel pattern and the external bar between them.

Cross-bar sandwiching: placing two internal bars in a crossed pattern and the external bar between them. This technique is used to cover the lower bilateral costal depressions.

Author: Hyung Joo Park, MD

References

Park et al. Ann Cardiothorac Surg 2016

Modified Ravitch Procedure

In the case of chondrogladiolar PC, the general concept of the modified Ravitch operation also applies. Once a subperidondrial resection of all deformed cartilage has been obtained, and the sternum has been corrected at the same level as the insertions of the intercostal muscles, one or two osteotomies of the anterior table can be performed if necessary, allowing the sternum to be fractured and displaced posteriorly, almost exactly as we explained for PE.

In cases of a chondromanubrial deformity (see also “Currarino-Silverman-Syndrome” in the subgroup “others”), a titanium plate is also recommended to repair the transverse osteotomy of the sternum, with which it is possible to obtain adequate correction and a better position of the chest wall (Figure 1a & b). In most cases the resection can be a larger triangle than a simple transverse osteotomy

Figure 1a & b: System of parallel plates to repair the transverse osteotomy of the sternum. This allows the young patient to have a sternotomy, if it is ever necessary.

To finish the procedure, the pectoralis major muscles have to be brought together, which requires a submuscular suction drainage for a few hours, and closure of the subcutaneous tissue and skin with running sutures.

Author

José Ribas Milanez de Campos, M.D.

References

Ravitch. J Thorac Surg. 1952

Sulamaa et al. Acta Chir Scand. 1959

Haller et al. Ann Surg. 1976

Mao et al. J Pediatr Surg. 2017

Shamberger et al. J Pediatr Surg. 1988